OPINION: Why the Vietnam Grand Prix has one of the Best Modern Layouts

First things first; F1 Needs long straights.

With the announcement of the Vietnam Grand Prix in Hanoi, reactionary outrage seemed only fitting for a circuit that has seen a complete makeover since the last time F1 suggested it would visit the region.

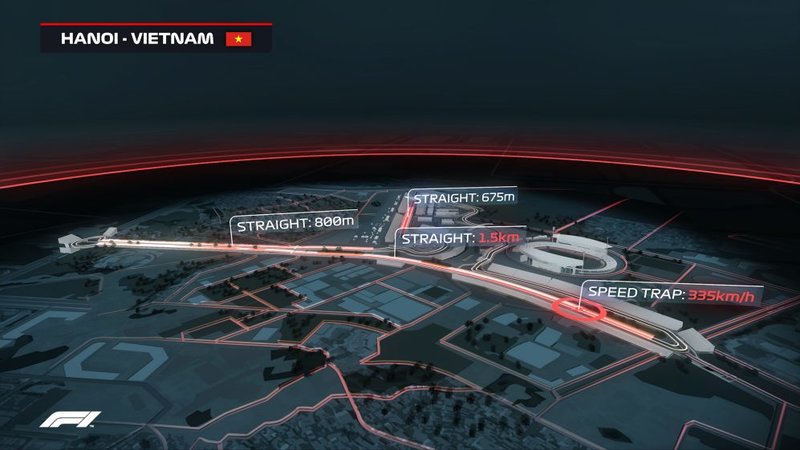

Three long straights, a twisty left-right section and a roundabout to negotiate was not what the traditional circuit racing crowd we after and social media response was typical of this. What’s perhaps less clear though is that this is a circuit that is designed to complement modern F1 racing.

Now, even I will admit it’s aesthetically unappealing. The long run between what looks like turn five and six with a roundabout at the end wreaks of corporate design and as a result, comparisons to Flamingos and Giraffe’s haven’t been unwarranted.

However, with DRS overtakes and aerodynamic efficiency being the name of the game, the organisers had to design something to this effect. F1 were quick to highlight the fact turn 16-19 will be modelled after Suzuka’s Esses (T2-6), but like their Japanese counterpart, this will not be where the major overtakes or noted action are.

F1 Tracks Need to be Built Differently

Modern F1 cars can only overtake successfully on flat out areas of track.

The last race at Mexico was a fine example, in which the majority of overtakes only happened at the end of the long start straight or the second run up to Turn 4. The Esses and Stadium section saw little past a few backmarkers giving up position.

Unlike the street battles of the 1980’s around Detroit or Long Beach, it’s almost impossible for F1 cars to keep so close to the car in front any more. Race strategy is built around the waxing and waning gap in order to preserve tyres.

Slow sections to race tracks are only effective if implemented just after a long straight when you’ve managed to force your opponent to the inferior line. This was most obvious at COTA, where Max Verstappen battled and defended his place to Lewis Hamilton. But even in this incident, the close wheel-to-wheel racing only came to an end when the track opened up onto the fast Turn 17. Many similar battles (including Verstappen’s illegal overtake on Raikkonen in 2017) also came to an end, due to this corner.

Graining tyres is another reason for this. Graining is nothing new, but the effect of the optimum line has been exaggerated in recent years, to the point where even backmarkers are reluctant to spend too much time in the dust.

The Tilke-led designers to the Hanoi track know this. You just need to look at the opening sector.

A sharp turn one onto a Sochi-esque T2 and T3 followed by a medium speed chicane that leads onto the first of the long straights. This section is designed for the chasing driver to remain close to the car in front and give them an advantage should the leading car make a slight error in their cornering anywhere through a complex that only has one clean line.

The sharp right at the end of the first long straight, onto the roundabout is another perfect example. Should an overtake occur off line the chasing car has the opportunity to carry more corner speed onto the second of the long straights out of Turn 7.

It’s a corner similar to that of Shanghai’s Turn 11 or the opening complex at Oschersleben (for our German enthusiasts.) Obviously, here is where the Baku comparisons start to become obvious and with good reason. The long straight in Azerbaijan may have become somewhat of a meme for many, but the late braking manoeuvrers into T1 and Lance Stroll & Valterri Bottas’ run to the line in 2017 have made up some of the circuits most iconic moments. Providing the braking zone into turn 11 near the stadium is wide enough, here is where we will see those iconic racing memories.

Even after this, a short straight ensures drivers cannot get away with dive-bombing into the corner and filling the track during a tight chicane section as we used to see at Korea into Turn 4.

Why not the Old Circuits

Korea of course opens the door to another argument; Why not bring back old classics?

Watkins Glen, Istanbul Park, Kyalami and even Imola. “What was wrong with these!” Well, to be brisk, the final two listed have all either been shut down or are nowhere near F1 standard. Both Watkins Glen, Imola and Kyalami have also had configuration changes to make them more suitable for club racing within their countries.

All F1 circuits require an FIA Grade 1 licence to host an event and for many former jewels, this is no longer a feather in their cap. Kyalami, Donington Park, Zandvoort, Long Beach (the new Indycar style) – All Grade 2, while Adelaide (what’s left) is Grade 3. The cost required to get these circuits up to standard are often not worth it for local governments with either no budget / incentive.

Length has also been a major issue.

Of the 40 Grade 1 circuits, fourteen of the longest have all hosted F1 at some point, with seven of the top eight currently doing so. On the opposite end of the scale, only 1 of the shortest 10 circuits (1 of the 6 if you exclude shorter configurations of longer circuits) currently host. The exception – Monaco. Only six current circuits are below 2.8 miles long and only Monaco is below 2.6. As F1 continues to expand, it’s clear that longer faster circuits are the way forward, two and half mile speedways do not provide the track space for modern racing.

Vietnam itself will be 3.4 miles long, well within the range. Of course, despite what I’ve said, there are exceptions which still fit the current criteria, most notably; Istanbul Park. Though this sadly is where money talks more than history or accomplishments.

This trajectory of old classics being shut down is certainly nothing new. Hockenheim’s old banking becoming shrub land is brought up every year for a few clicks, while street circuits such as Detroit, Caesar’s Palace or Adelaide have had city planning changes ensuring racing would be impossible on the original layout.

European Circuits don’t Provide a Challenge

The Hanoi circuit may seem as if it’s just cherry-picking elements from already famous circuits, but as the racing changes, these traditional European classics are becoming increasingly obsolete. Especially if the newer designs take the most exiting parts from each.

For anyone arguing that Formula One itself struggles to produce overtaking look at the crop of current European circuits. Catalunya, Hungaroring and Paul Ricard. Other than Bottas and Vettel’s first corner crash in the later, all have been tame races this year, with the Spanish Grand Prix a notable event that struggles to produce the fireworks.

They’re not alone. Both Melbourne and Suzuka (staples of the calendar) will be remembered more for incidents that happened between drivers than the action produced on track. All of this is without bringing up the king of the procession; Monte-Carlo.

It’s all very well criticising Sakhir or Sochi, as both are considered products of the modern Tilke era, but fans are far more reluctant to raise protest when it’s on circuits that have been on the calendar Pre-1999.

An argument could be made that this year’s title defining moment at Hockenheim was due in part to the changing track surface, exacerbated by the oncoming rain, while of course circuits that provide a physical challenge (like Spa or Singapore) are obvious counterpoints. However, like Spa, these are only enhanced by the threat of lingering precipitation. Circuits need to stand up to their own merits.

So finally to Baku.

Baku, shouldn’t work as an F1 circuit. The pit lane is traditionally at the wrong end of the finish straight, the kinks in the straight have not enough run-off in the event of Webber-Valencia 2012 style crash, most corners have minimal escape roads, the old town is too narrow and it changes style so regularly that tyre wear is common.

Yet, Baku has produced some of the best races over the past three seasons. In fact, the circuit is so unsuitable for F1 that it works, it’s become it’s own challenge, like Spa or Singapore as said previously. This is what Vietnam can only hope to emulate. In reality the partly three lane wide motorway will not make overtaking a black and white understanding, but could open the door to a double slipstream down the main straight. A move Baku has almost been able to pull off.

Of course all of this does ignore that the biggest issue restricting F1 cars in the current era is not the tracks, but the car design themselves.

Vietnam may not have been an F1 fans first option when it comes to exotic destinations, but the varying track surface and speeds, along with a layout designed for the modern race car could make Hanoi a viewers favourite in years to come.

![Private: [ID: 71rYi-xncgM] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/private-id-71ryi-xncgm-youtube-a-1-360x203.jpg)

![Private: [ID: 1SfHxvC8Doo] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/private-id-1sfhxvc8doo-youtube-a-1.jpg)

![Private: [ID: H6XRkf6kROQ] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/private-id-h6xrkf6kroq-youtube-a-1-360x203.jpg)

![Private: [ID: Kb6w-qAmKls] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/private-id-kb6w-qamkls-youtube-a-360x203.jpg)

![Private: [ID: CcpwYw20k3k] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/private-id-ccpwyw20k3k-youtube-a-360x203.jpg)

![[ID: x1SiRC5jhW4] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/id-x1sirc5jhw4-youtube-automatic-360x203.jpg)

![[ID: lMZ8lAeLubk] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/id-lmz8laelubk-youtube-automatic-360x203.jpg)

![[ID: GAYCcnqyFo4] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/id-gayccnqyfo4-youtube-automatic-360x203.jpg)

![[ID: Gg142H296QY] Youtube Automatic](https://motorradio-xijqc.projectbeta.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/id-gg142h296qy-youtube-automatic-360x203.jpg)